When to use

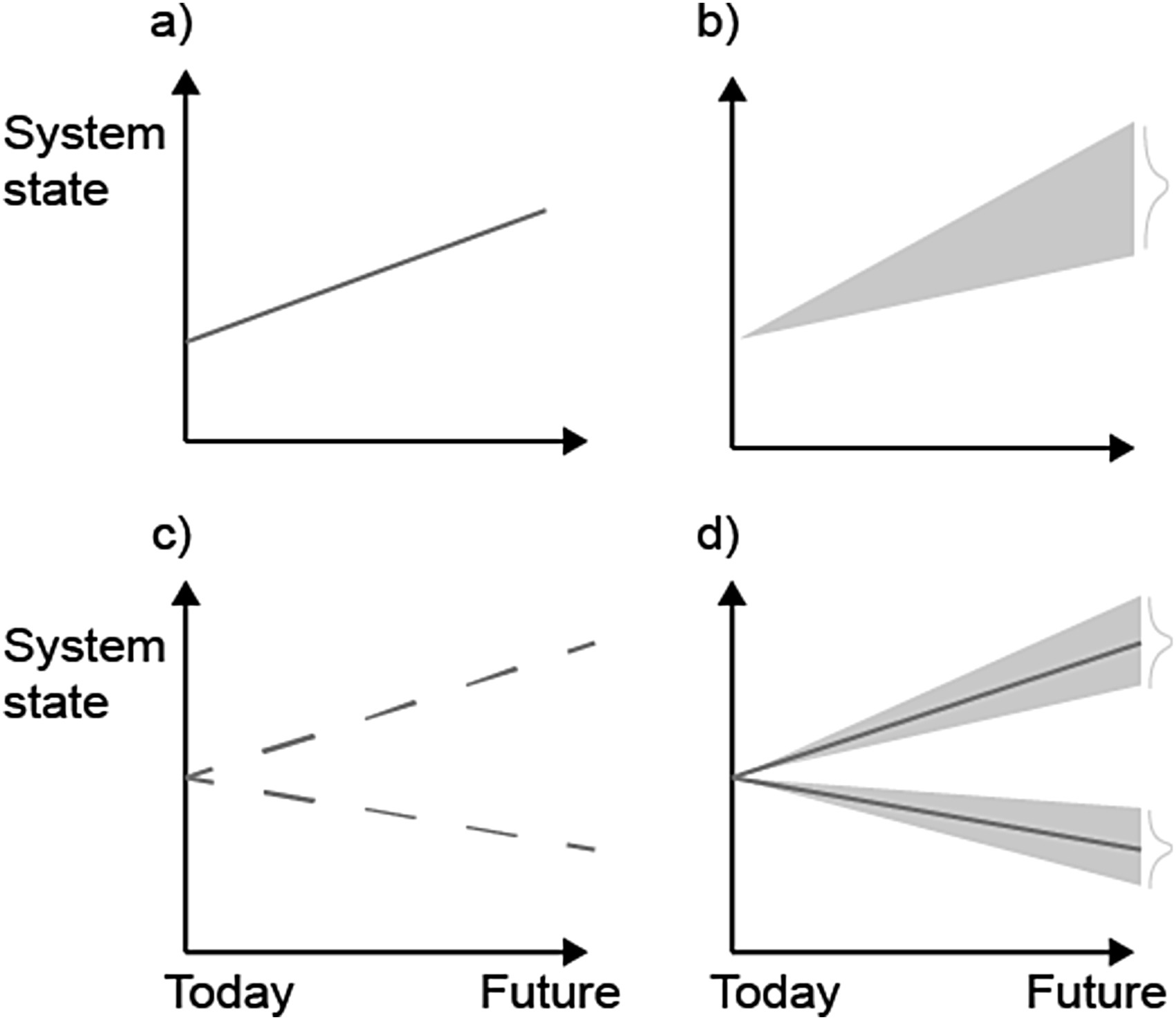

Describing uncertainty in terms of multiple plausible futures recognises that there is certain information we do not have (see (a) and (b) in the figure below):

- it does not make sense to plan for a single best projection of the future

- we cannot use probabilities, e.g. to select a solution that performs well on average, guarantees a specific level of reliability or minimises expected shortfall

- the future is not bounded, so we cannot simply plan for the worst case.

Instead, we have to act and plan as if any of the multiple plausible futures could occur - and possibly others (see (c) in the figure).

It may be that we have more information about some aspects of the future, such that "multiple plausible futures" may be mixed with other ways of describing the future (see (d) in the figure).

Given that "multiple plausible futures" is a way of describing uncertainty about the future, in principle it can be used even if one future is considered more likely than all others, or bounds and probabilities could be assigned. However, the result is that this extra information is discarded (e.g. because it is considered insufficiently unreliable), which may not be what you are after.

Multiple plausible futures are commonly encountered in strategic decision making in the face of climate change and global change, and where there are known tipping points with unknown thresholds.

How

The basic element for handling multiple plausible futures is a "scenario", which describes a future either in terms of states of the world (e.g. values of different of variables), or coherent storylines. Each scenario should be based on different assumptions about the future.

Scenarios are often quantified using computational models. In that case, we distinguish between "model scenarios" that capture a best available understanding of a system from model scenarios that explore different assumptions about the future, which we refer to as exploratory modelling.

In the context of multiple plausible futures, "decision making" means that we need to develop a single plan of action that somehow achieves its objectives regardless of which of the plausible futures occurs. There are two key strategies:

- "Robust decisions" literally perform well across a range of scenarios. Their robustness can be measured, or we can evaluate how their performance varies across scenarios, including circumstances where the plan of action fails.

- "Adaptive decisions" recognise that the single plan of action can actually change over time as the future unfolds, resulting in "adaptive pathways", which may involve assessing the value of information or identifying triggers to change direction.

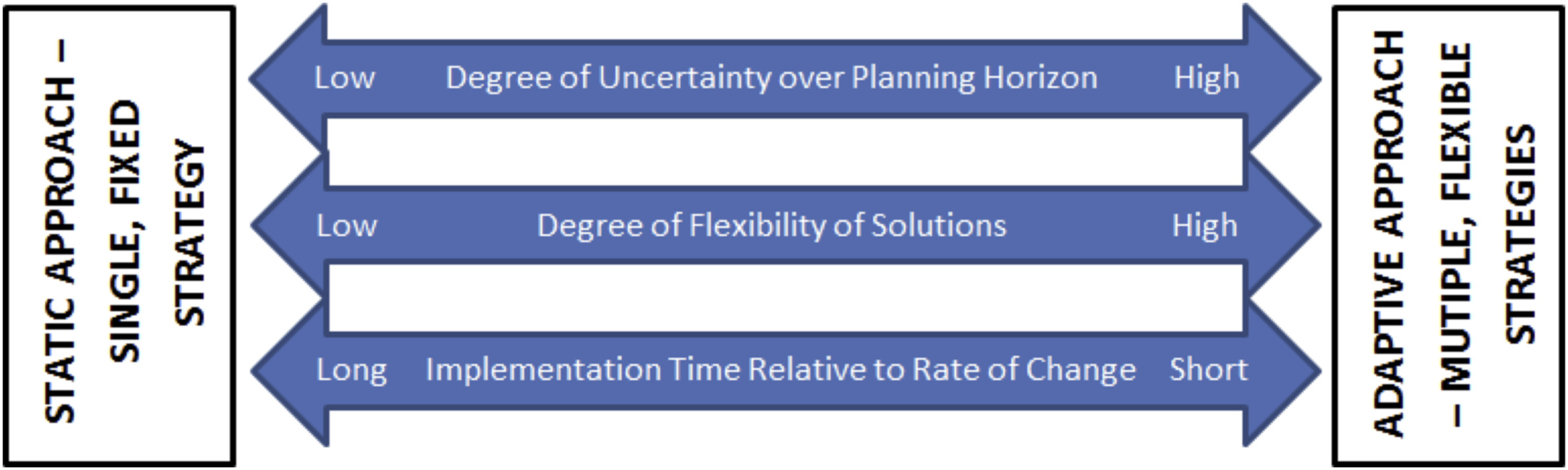

Adaptive solutions can be robust, so the adaptive approach in fact contrasts with a static, single fixed strategy, which may be preferable if uncertainty over the planning horizon is not too high, there is limited flexibility in the decision to be made, and it would take too long to change the plan of action.

Robust and adaptive decisions allow a course of action to be selected because they provide confidence that we have considered how that course of action might play out across plausible scenarios, and the course of action is either superior to alternatives (i.e. it is an optimal solution), or meets all requirements (i.e. it is a "satisficing" solution).

As a decision maker, if you'd like an analyst to help identify robust or adaptive decisions, ask for:

- Exploratory modelling and scenarios to explore how the future might unfold under different assumptions

- Evaluation of robustness, stress testing or vulnerability analysis of decision alternatives

- Design of adaptive pathways, monitoring plans or identification of triggers